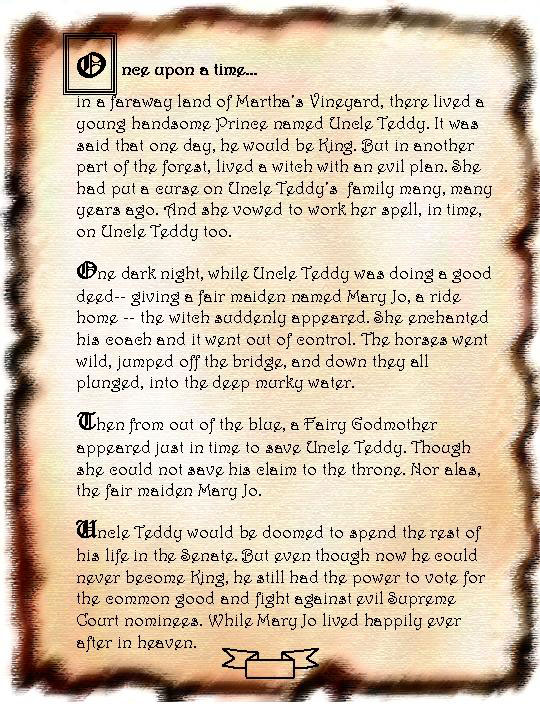

February

2006

Ted Kennedy Has

Written a Children's Book

We came across a press release

last month indicating that:

“Ted Kennedy has

written a children’s book, My Senator

and Me: A Dog’s-Eye View of Washington, D.C.,

to be released by educational publisher Scholastic

this coming May.”

In so doing, the senior Senator from Massachusetts

joins an ever growing and diverse list of celebrities who

have penned children’s books. They include the likes

of: Jerry Seinfeld, Julie Andrews, Bill Cosby, Jay Leno, soccer

star Mia Hamm, former NY Mayor Ed Koch, Dr. Laura Schlessinger,

Duchess Sarah Ferguson, Jimmy Carter, Director Spike Lee,

James Carville, Katie Couric, John Travolta and even Madonna

and…we’ll stop right here. You get the idea. A

lotta lotta people!

The press release goes on to state that:

“The book explains how a bill becomes

law; the roles of Congress and the Senate in the U.S.

system of government.”

This 56 page book promises to be, in a word—

B-o-o-o-o-r-r-r-r-r-ing!!

And this is really too bad, as the Senator is

sitting on one heck of a story that can be told in just one

page, and yet be every bit as adventurous as anything J. K.

Rowling can turn out.

For example, in just taking a blind stab at

this, we already believe we’ve come up with something

a whole lot more compelling than what the Senator has planned.

Here goes.

*

*

*

Writer’s

Block or… Six Authors in Search of a Character?

Having finally gotten around

to reading what is considered the classic novel of

the immigrant experience in early 20th century America, Call

It Sleep by Henry Roth, we

found it indeed to be fabulous and worthy of its reputation.

But upon finishing this robust book with its effusive prose,

we could not help recall hearing, that this is the same Roth

who had had such a notorious case of Writer’s Block.

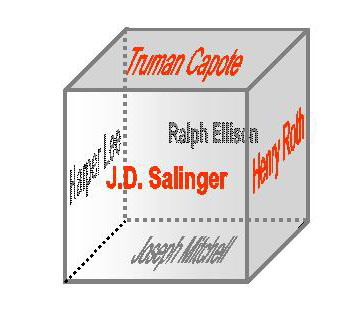

This in turn led us— off the top of our

head— to quickly number five other equally riveting

cases of WRITER’S BLOCK. Classic cases of important

writers of a generation, who apparently suffered from this

malady big time. Their names are inscribed in the literary

Rubik’s cube above.

As a poet and writer, this of course, would

be a subject close to our heart. But it can also be of interest

to anyone who has ever experienced other forms of so called

“blocks,” or wondered about what it is that nourishes

or suffocates the creative process. And let’s face it,

there is a certain comfort in the messages that read loud

and clear: we’re not alone!… and

that yes indeed, misery does love company. Especially

when the companions are geniuses who can’t get their

car out of “Park.”

First off, a working definition of what we mean

by Writer’s Block, is in order. While there is no hard

fast definition—in fact some don’t even think

it is something that exists—essentially for our purposes

here, it consists of four components:

• a writer of tremendous

talent

• who has been acknowledged and rewarded by literary

experts and the general reading public alike

• who has not published anything over an extended

period of time

• for no apparent or stated reason

The source of much of the information in putting

this piece together, was an excellent article that appeared

in The New Yorker (“BLOCKED Why do writers

stop writing?” By Joan Acocella; issues June 14 and

21, 2001; heretofore referenced by TNY).

http://www.newyorker.com/fact/content/?040614fa_fact

Henry Roth (1906-1995)

His first novel Call It Sleep

was published in 1934 when he was twenty-eight. It got little

notice. It was reprinted 30 years later (1964) in paperback

and became a sensation.

He didn’t start on his second novel until

1979 which turned into a four volume tome entitled Mercy

of a Rude Stream; the first volume of which

appeared in ’94 a year before his death.

In effect, he went 60 years between publication

of his first and second novel! And then seemingly, he tried

to make up for lost time, by going out in one last big hurrah.

He had, by the way, the good sense to call his autobiographical

work, novels and not memoirs, lest he get “Frey-ed”.

(We couldn’t resist).

Joseph Mitchell (1908-1996)

This writer is particularly close to our heart,

as he wrote pieces about real people and real places, many

of which we knew from our wondrous youth growing up on the

Lower East Side of New York.

We will quote TNY

piece here directly, which confirms what we once heard Tina

Brown, former editor of that magazine, say at an advertising

luncheon one afternoon.

“A story that haunts the halls of

The New Yorker is that of Joseph Mitchell who

came on staff in 1938, wrote many brilliant pieces, and

then, after the publication of his greatest piece, ’Joe

Gould’s Secret,’ in 1964, came

to the office almost every day for the next 32 years,

without filing another word.” (The underline

is ours).

Tina said that they would hear typing…but

alas, no copy ever emerged from behind that closed door. TNY

goes on:

“In a series of tributes…upon

Mitchell’s death…Calvin Trillin recalled hearing

once that Mitchell was ‘writing away at a normal

pace until some professor called him the greatest living

master of the English declarative sentence and stopped

him cold.’“

Imagine what would have happened if this professor

had spoken ill of him?

Truman Capote (1924-1984)

“Rediscovered” via the excellent

movie Capote and Philip

Seymour Hoffman’s extraordinary performance

as the title character, we now all know that he never finished

another book after the publication of In Cold

Blood in 1966.

For the last 18 years of his life, he was at

work— in fits and starts— on what was to be a

major novel Answered Prayers. But

alas, it was still incomplete at the time of his death; the

prayer of matching his previous success going unanswered.

Of course with Capote there is always the issue

of his alcoholism. In fact it seems to be an occupational

hazard. TNY piece notes that five

of the seven native-born Americans awarded the Nobel Prize

for Literature, were alcoholics. But it does raise a question.

To wit:

“when an alcoholic writer stops writing,

do we call this a ‘block’ or just alcoholism?”

Harper Lee (1926- )

A childhood friend of Capote’s, she too

is a very prominent figure in the Capote

movie as she was in Truman’s life.

She published her first novel, To

Kill A Mockingbird in 1964 at age 34 and it

became an immediate best seller and won a Pulitzer Prize.

But beyond that, it has been a fixture on required reading

lists of High Schools and Junior High Schools in America for

these past 45 years. And, of course, it was turned into an

Academy Award winning film of the same name in 1962.

She never published a second novel.

She continues to live a quiet, almost reclusive

life in Monroeville, Alabama, where she was born and raised.

She did come to LA in June of 2003 for Gregory Peck’s

Funeral mass and memorial at Los Angeles Cathedral (where

the actor’s body is interred). Our parish priest reports

that she is a sweet and endearing woman, and there are no

apparent outward signs of eccentricities which would suggest

why she was “just” a one-book wonder.

That we all could have but one hit in our lives,

of such enduring magnitude: 10,000,000 copies sold since 1960

making it one of the best-selling novels of all time..

Footnote: And so a day

after writing this, there’s a picture of Harper Lee

right on the front page of The Arts section of The New York

Times (January 30, 2006) at an awards ceremony for an essay

contest on the subject of “To Kill A Mockingbird.”

Well we did say she was almost a recluse.

Ralph Ellison (1914-1994)

Ellison was also a hit right out of the box.

His first novel published in 1952, Invisible Man,

was a best seller.

“It was an ‘art’ novel,

a modernist novel, and it was by a black writer. It therefore

raised hopes that literary segregation might be breachable.

In its style the book combined the arts of black culture—above

all, jazz—with white influences: Dostoyevsky, Joyce,

Faulkner.” (TNY)

Beyond being just a writer, he was virtually

a hero, being awarded the Presidential Medal of Honor by Eisenhower.

But there would be no second novel. This, despite

having worked on it for 40 years!

When he died at the age of 80, he left behind

more than 2,000 pages of manuscript and notes. His executor

pieced together a novel out of it, something called Juneteenth

and published it in 1999. Hardly a success.

J(erome).D(avid).

Salinger (1919- )

Perhaps one of the most enigmatic writers in

the history of American Letters, he burst on the scene in

1951 with The Catcher In The Rye.

Word for word, this has got to be one the best of our literary

classics— it’s only about 200 pages long. Salinger

tended to “write short”. Short stories; short

novels; novellas.

After “Catcher” hit the scene, Salinger

retreated from public view and began a life as one of the

most interesting and sought after recluses this side of Howard

Hughes. Going in search of Salinger has become a sport for

many of his still rabid fans. Some of whom, unfortunately,

are a bit misguided and read their own message into the book.

On the night when Mark Chapman murdered John Lennon, he was

toting a copy of The Catcher In The Rye, which he

was calmly reading when the police arrived on the scene.

While Salinger has not published anything

in over 40 years, there is much speculation that he has been

writing all this time. And there is always the hope that upon

his passing, this work will be made public. He is now 87.

And in his longevity, you get the sense that he is purposefully

busting our chops.

*

*

*

In the Department of:

Short-Poem-for-a-Short-Month-having-nothing-to-do-with-Shortness

Antithetically Speaking

Without the arts

we are the ants:

heavy lifters

of crumbs;

the masters of

the commute to and fro;

noble

negligible;

crashers at The Big Picnic.

*

*

*

Master of American Comics

and one Winsor McCay

For those of you living in LA, there is a wonderful exhibit

in progress until March 12, 2006 entitled Masters

of American Comics, in joint display at The

Hammer Museum in Westwood. www.hammer.ucla.edu

and The Museum of Contemporary Arts www.moca.org

.

Featuring the works of fifteen “cartoonists”,

the raison d’etre for this exhibit is to provide insight

into the medium of comics as an art form. Or to quote

the press release:

“This exhibition has been founded on the premise

that comics are a bona fide cultural and aesthetic practice

with its own history, protagonists, and contribution to

society, on a par with music, film, and the visual arts,

but is still in need of the kind of historical clarification

that has been afforded those other genres.’

Amen. Hey, you had us on: “This exhibit has been founded…”

For we grew up with the “Sunday funnies” and the

comics in our lives; a key source of entertainment in a pre-video-game

age. And so we were familiar with many of the comics or their

illustrators that were presented in this exhibit, including

the likes of Dick Tracy (Chester

Gould), Popeye (E.C. Segar), Peanuts

(Charles Schulz), Terry and the Pirates and Steve

Canyon (Milton Caniff), Gasoline

Alley (Frank King) and Mad Magazine

(Jack Kurtzman).

And then there were those we had never heard including one

in particular that caught our eye and captured our imagination:

Winsor McCay (1867-1934).

He is acknowledged to be the first master of both the comic

strip and the animated cartoon. His masterpiece was a comic

strip that was first published in the New York Herald in 1905

entitled Little Nemo in Slumberland.

The man was so far ahead of his time he might have been a

product of the 60’s what with his surrealistic approach

and use of a sort of “op art”, his refusal to

“stay within the lines” and a style that suggests

the use of hallucinogens while at the drawing board. The imagery

of many of his strips is at once filled with lovely childhood

evocations and yet a sense of the dark, the grotesque, the

foreboding.

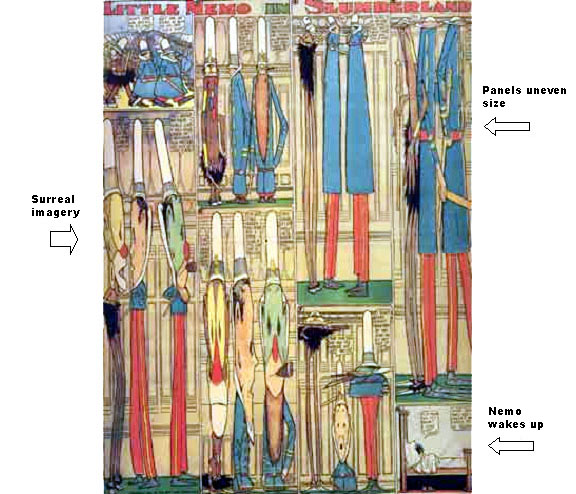

The premise was always about a young boy, Nemo, who upon

falling asleep, would drift off into a bizarrely graphic and

distorted dream, from which he would awaken in the final panel.

The reprint below from 1905, will provide some sense of the

strip, though the captions here are not readable.

And now Winsor McCay is in the process of being rediscovered

big time. A giant book retailing for $150 was published in

2005 with a second printing due in March of this year.

Winsor

McCay’s masterpiece, Little Nemo in Slumberland, as

it has never been reproduced before. A magnificent limited

first edition hardbound volume with Nemo's best from 1905-1910,

FULL original newspaper size. An essential piece of American

cultural history. 16x21 inches, 120 pages. Winsor

McCay’s masterpiece, Little Nemo in Slumberland, as

it has never been reproduced before. A magnificent limited

first edition hardbound volume with Nemo's best from 1905-1910,

FULL original newspaper size. An essential piece of American

cultural history. 16x21 inches, 120 pages.

We invariably can’t help but wonder whenever looking

back at a piece of pop culture that was so ubiquitous in its

time, what will happen to the “big hits” of our

time. Will South Park, for example,

be rediscovered and be the subject of a museum retrospective

100 years from now?

*

*

*

fini

|